Mae: Voice Interaction Prototype

Product design, multimodal & voice designMae is a conversational toy for children and adults that projects the night sky and can tell you all about the stars, constellations, and the mythologies behind them. Maria Randall and I wanted to try our hands at the voice design process, and creating a testing environment to verify and refine the fundamentals of Mae’s voice interactions. We decided to focus on pauses, confirmations, and error states

TIMELINE: 8 weeks

TOOLS: Whiteboarding, Python, Premiere

TEAM ROLES:

DILLON: Voice UI, user testing, UX research, filming

MARIA RANDALL: Voice UI, user testing, UX research, identity & illustration

JUDILEE HAIDER: UX research, storyboarding, animation

Judilee Haider and Maria Randall initially conceived of MAE as a conceptual interactive product for a prototyping assignment in our Motion Design class at Seattle Central Creative Academy. Maria and I had been chatting about and exploring design solutions in the voice and multimodal design space—so we decided to explore building out MAE’s interactions beyond the preliminary conversation flows she and Judilee had put together as part of the original project.

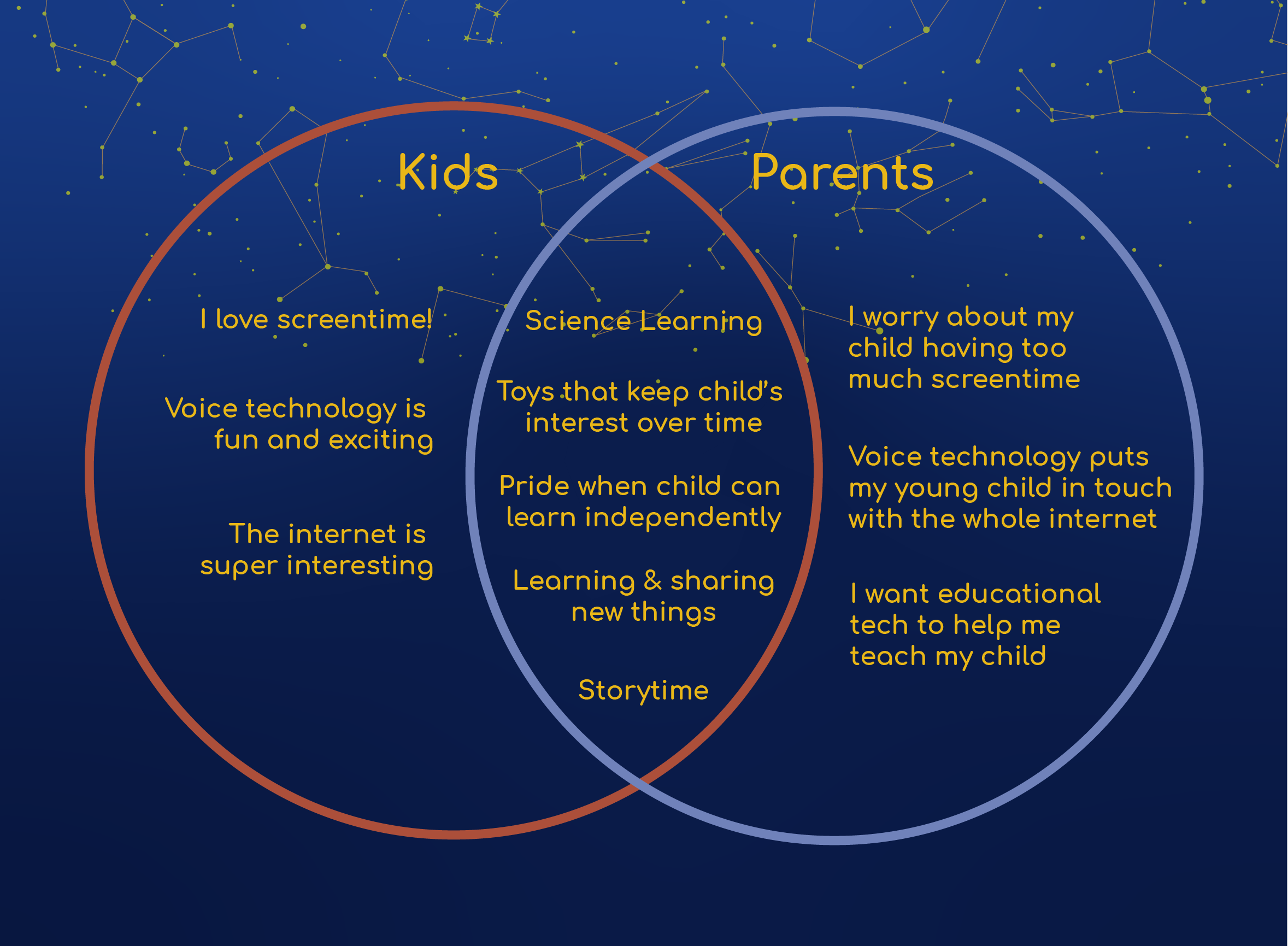

We wanted to address the problem of tech and screetime-based toys impairing child development (JAMA Network). We saw an opportunity to create a tech-based educational experience that was actually good for kids. Mae’s voice interaction and wall projection interface allows for a screen-free, multimodal, immersive, and healthy educational experience for kids to learn about the stars in the night sky.

Mae is still in essence a toy—therefore our user needs had to be the overlap between the child who interacts with the product, and the parent who sanctions and purchases the product.

Voice Design

testing process

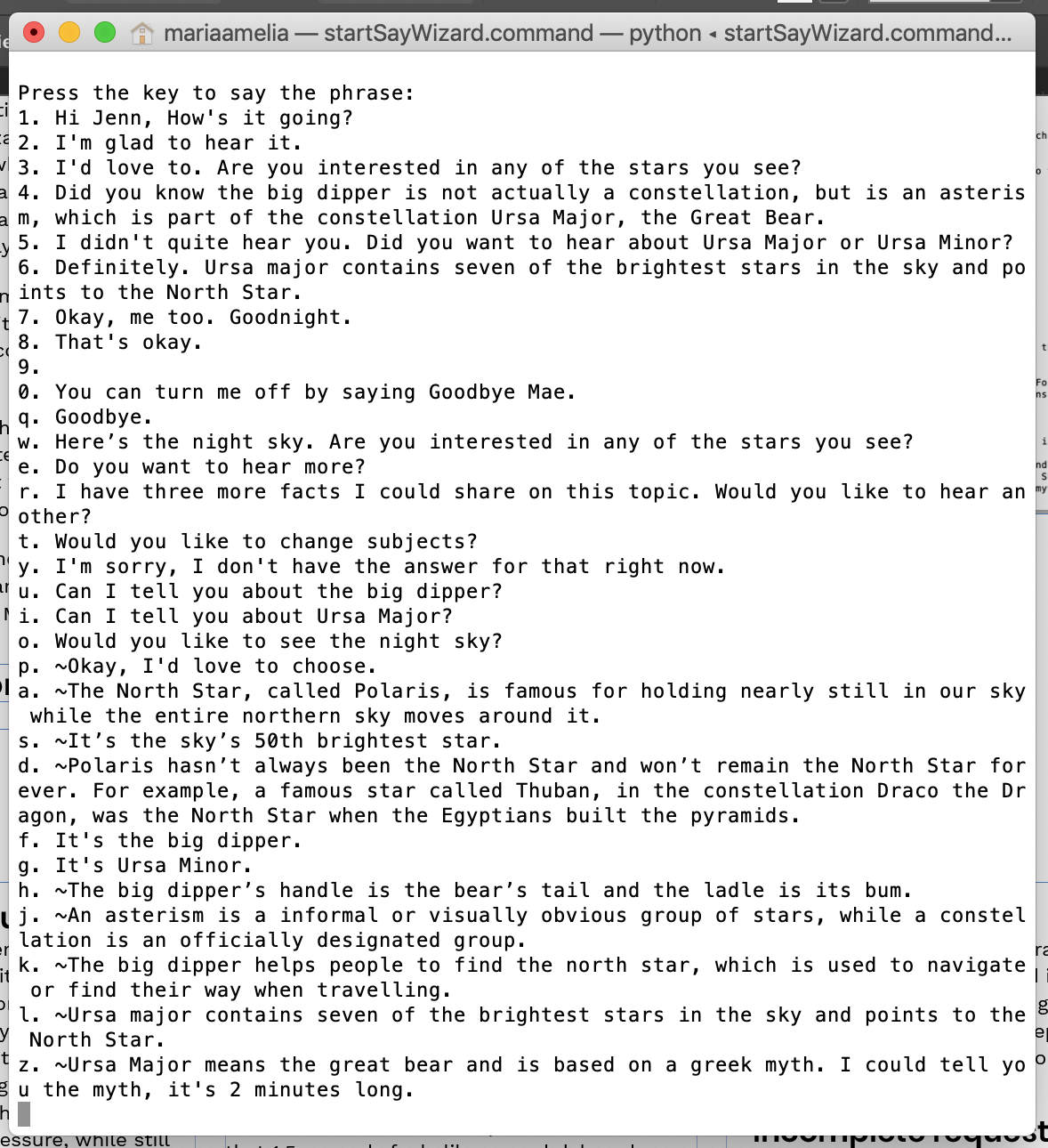

After trying out a few different approaches—from the lowest-tech methods (a completely analog testing) to the highest-tech (many thanks to the kind folks at Orbita who gave us a sandbox version of their voice design platform to work with) we ended up somewhere in between, but skewing low-tech.

We did what is referred to as “Wizard of Oz testing”, i.e. we had a guy behind the curtain. We set up a python script that allowed pre-built responses to be played at the touch of a laptop key, which were sent to a Bluetooth speaker into a physical Mae prop we built out of a small cardboard constellation globe and a lightbulb. We spent days whiteboarding “happy paths” until we got a bank of flow responses with which we felt we could get actionable insights from vis testing on reeal people. For the projected UI, we just held up a large paper printout of what the user would see on the walls and ceiling of their bedroom.

After our first round of tests we came to a few critical conclusions:

1 Mae needed to sound more friendly and conversational.

2 She needed to guide the user into an interaction by prompting them with an option immediately when she wakes up.

3 We needed to A/B test for how much she should prompt a user vs. how passive she should be.

4 We needed to A/B test for pause length: how long should she wait for the user?

Through our rounds of testing we had to make drastic changes to the script and sometimes to the physical considerations of the testing environment. After the the first few scripts proved to be far more complex to control and execute than we anticipated, we learned to create shorter scripts that would wholly focus on one small aspect of each interaction. Mae is fundamentally a different type of interaction than a product like Alexa—but we were able to cross reference our results with some of the newfound best practices in voice design we had researched for products like Alexa, Google home, and Siri.

1 Mae needed to sound more friendly and conversational.

2 She needed to guide the user into an interaction by prompting them with an option immediately when she wakes up.

3 We needed to A/B test for how much she should prompt a user vs. how passive she should be.

4 We needed to A/B test for pause length: how long should she wait for the user?

Through our rounds of testing we had to make drastic changes to the script and sometimes to the physical considerations of the testing environment. After the the first few scripts proved to be far more complex to control and execute than we anticipated, we learned to create shorter scripts that would wholly focus on one small aspect of each interaction. Mae is fundamentally a different type of interaction than a product like Alexa—but we were able to cross reference our results with some of the newfound best practices in voice design we had researched for products like Alexa, Google home, and Siri.

In the 5 weeks (6-8 hours per week) we gave ourselves to build our voice design process and practices from the ground up, we were amazed at how deep the process became—and how few concrete product features we came out with in that limited timefram. We would’ve loved a larger team and more time!

With our findings, we determined Mae needed to wait 4 seconds before prompting a silent user further with a question or follow-up. This was longer than the recommendations we gleaned from our research; but again, Mae is, at her core, an exploratory and educational experience, and the user will often be lying on their bed or sitting and looking up at the “stars”. Naturally, a 4-second pause in this type of situation will feel relatively quick compared to a 4 second pause from Alexa when you’re, say, trying to figure out what time a restaurant opens.

Below are the primary product features we came out with from our testing.

With our findings, we determined Mae needed to wait 4 seconds before prompting a silent user further with a question or follow-up. This was longer than the recommendations we gleaned from our research; but again, Mae is, at her core, an exploratory and educational experience, and the user will often be lying on their bed or sitting and looking up at the “stars”. Naturally, a 4-second pause in this type of situation will feel relatively quick compared to a 4 second pause from Alexa when you’re, say, trying to figure out what time a restaurant opens.

Below are the primary product features we came out with from our testing.

Teaching users

How passive should Mae be? How does she teach a user how to interact with her? Does Mae prompt a user after she shares a fact or story—does she wait quietly or ask the user if they’d like to hear more right away? We want the experience to feel open-ended and low-pressure, while still teaching users how to make the most of their interaction with Mae.

This is an example of Mae teaching a user what she does upon initial wake.

How long are her pauses?

Is this longer in children than in adults? This proved our most fertile ground for testing, and it is different in a mult-turn dialogue, when she first wakes up, and after she’s shared a fact or story.We’d read that 1.5 seconds feels like a good delay when the user is expected a response from Mae, but what about after Mae had replied, and is waiting passively to see if the user will interact with her further?

We decided that Mae should prompt a user after 4 seconds of being woke, if they hadn’t made any requests, with “Would you like to see the night sky?” or similar, and that she would prompt a new user after each fact with “Do you want to hear more?” or variant, and an experienced user only some of the time.

Errors and incomplete requests

It’s important to have Mae reiterate whatever slot or word she has recognized in order to move the user forward and not get stuck in a loop—we know children often repeat the exact same wording of their request for long periods when they are not understood.

We determined that she should give the user options if she can hear the intent, following the “one breath” rule of thumb, after waiting 4 seconds, in case they correct themselves.